“Is this John? I’m Kathleen’s nurse at Taos Living Center. I need your permission to send your wife to the ER at Holy Cross. She doesn’t look good at all.”

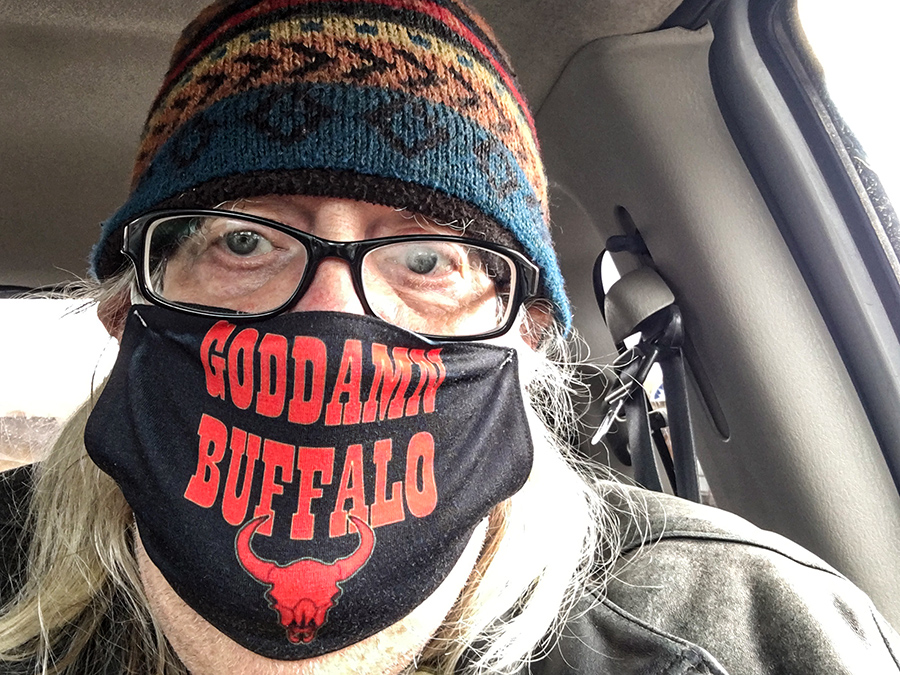

Me, buying lampshades at fucking Walmart, yanking my mask off to speak clearly into the phone. Everyone has disappeared, the world gone black…

“I don’t understand. I’m supposed to bring her home from stroke rehab tomorrow!”

“Her vital signs are very bad. Pulse rate 25, oxygen 42. She’s declining.”

“Declining? What… Oh God. I’ll be there right away!”

“It may take 30 minutes for the ambulance to transfer her. I’m calling now.”

I was almost at the register. Hung up and paid. Out the door and in the car. Old men and fat ladies shuffled by. It was a sunny day. Thirty minutes? I’d better go home first, I thought. I’ll need long pants and a sweatshirt at the hospital. And a phone charger, and my laptop. Maybe a sandwich, change of underwear.

Halfway home, trying to breathe. Am I really going all the way back? The phone rang once again: “Mister Farr? This is [another nurse] at the Emergency Department at Holy Cross. Your wife is declining rapidly. The EMTs just pulled in. We’ll have her here in 30 seconds…”

“I’m on my way!”

What the hell was going on?

Backed into a driveway and turned around, let a pickup truck go by. A slow one, driven by an old guy with a VFW license plate. He crept so slowly over the speed bumps by the little church I almost rammed him. If I’d had a gun I might have used it. Arrived at Holy Cross, parked close, pulled on my mask, and strode in through the plague door. Two people stood up to take my temperature and ask me questions. Oh no, you don’t.

“My wife is dying in the emergency room!”

“I’ll take you…”

So many corridors. It’s just a little hospital. Are they all like this?

“In here. Can I get you anything?”

Just then they wheeled her in and pulled the blanket back. She was in a tight fetal position, eyes closed, mouth open, all her color gone. I was sure that she was dead. Oh God. She wasn’t though. I could see her breathing, and she moaned on every exhalation.

[Shallow breath, “nnnghh,” two seconds, another breath, “annnghh,” two seconds… ]

They took blood and urine samples, hooked her up to monitors, stuck needles in her wrists, taped an oximeter sensor on her finger. Someone else came in and took an X-ray of her lungs. That wasn’t easy. Nurses came and went, glancing at the dancing colored lines. Competent-looking doctors showed up. One asked, “And you are…?”

“John Farr. I’m her husband.”

He flipped through pages on a clipboard. “I’ve been conferring with Dr. [so-and-so], the one who saw her last time.”

He told me that the chest X-ray showed her lungs were massively infected, then turned to his colleague and went on in a softer voice. I made out “ejection fraction, 30%” because I already knew that and I swear they rolled their eyes.

“What happens now?”

“Well, we can send her back to Taos Living Center, and—”

“We’re never going there again!”

“Are you prepared to take her home?”

“No way, no…”

“Then we’ll work on getting her admitted and make her comfortable.”

Say what?

They spun around and left. A nurse showed up with coffee. They wheeled her to another room and closed the door. Shallow breath, “nnnghh,” two seconds, another breath, “annnghh,” two seconds. She had an oxygen mask on now, more color, and was stretched out on her back, but her eyes were barely open and I couldn’t tell if she could hear me. “Nnnnghh,” gasp, then two seconds. I counted every pause. She moved around a little and tried to pull the sensors off.

This went on for several hours. I was freezing in my shorts. A nurse brought me a blanket that I wrapped around my shoulders. Finally they had a room for us down endless corridors. A different nurse hooked up a Tylenol IV, the moaning stopped, and yet another doctor knocked and introduced himself.

The full import of “make her comfortable” hadn’t registered yet, but the latest doctor said it wasn’t bad lungs but a second stroke that cut her down. He recommended morphine. I consented after he agreed to only half a dose each time. I didn’t want her knocked out, see, if we could talk. It calmed her and the gaspy inhalations weren’t so harsh.

Someone from the kitchen brought me food. I wolfed it down. But something had changed from one room to the next. She wasn’t getting nutrients or fluids. No sensors stuck onto her chest, no oximeter wired into a console, no instruments. Just a single IV port, a catheter, a urine bag. Oh no.

God help us, they were only feeding me!

By Saturday night I was tired enough to wish the whole world dead. No exceptions, either. Nodding off every minute. I talked constantly to Kathy who never shifted her position, breathing in that way that people who are dying do. My sister Mary the nurse was driving up from Tucson with her dog. “Tell Kathy I’m coming!” she texted from Hatch at 3:14 a.m. I did.

Mary showed up in the morning, said goodbye to Kathy, went away, came back. We talked and talked. I hadn’t seen her since forever. All this time Kathy was just lying there, mouth open, breathing like a fish washed up on the sand. Hearing is supposedly the last thing to go. My sister thought it might do Kathy good to hear us laughing, like she’d know we’d be all right. That made me feel a little better, but of course we couldn’t tell.

By late Sunday night, I was so exhausted I thought my heart would quit. Kidneys, liver, something, blood flow from my ears. Maybe I’d lose consciousness and split my skull. Kathy was either sleeping or too far gone to notice. I pushed my recliner up against her bed and curled up in a ball. I was dead already. If she made it through till morning, we could say goodbye, otherwise I’d wake up and find her cold.

Someone else was in the room. David, the tall nurse, with a stethoscope. I saw sunlight on the windows. He checked her heart and watched the quiet little gasps. “She’s close,” he said, and left. I got up, pushed the chair away, and knelt down by her bed. The next 90 minutes were the most intimate and powerful we ever had.

She was conscious. Her mouth was open underneath the oxygen mask. I saw black patches on her tongue and lips from circulation shutting down. Her eyes were open, barely. Maybe she could see. She might have moaned, I don’t remember. What I do is that she tensed her back like she was trying to sit up. I put my arm around her back and lifted. (My hand knew every bone.) She had one elbow on the bed to give support and reached up with her other arm to pull my shoulder. Her head fell over on my chest and she relaxed. Her breathing got a little softer while I talked. We stayed that way a long time.

I had to lay her down again but slid my arm behind her neck to hold her head so we could see. I’d cried a lot but something changed. Her breathing had become more agitated. I remembered my sister telling me that sometimes dying people need to know their loved ones will be all right so they can go. The gown had slipped from her left shoulder. Her skin was warm and beautiful. All at once I wasn’t worried. The love poured from me like I was on fire. I told her I would be okay, that I would write a book about us, that our love was greater than our bodies and would never die. Her respiration slowed and all was softer. She shot an image right into my brain to tell me where she wanted to be buried. I got down nose to nose with her. We looked right in each other’s eyes and held it. I didn’t talk or cry.

The way it went from there was gentle as can be. The pauses in between her breaths grew longer until I knew to lay her down. I took off the oxygen mask, fluffed her hair some with my fingers, stood up, and pushed the button to call the nurse.

All this time we’d been left totally alone. I told her everything, far more than written here. I know she heard me and she hears me still.

“Would you like the window open?” I heard someone say. (The nurse, of course.)

“Uh, sure. That would be real nice.”

“People in Taos like to do that when someone passes. You know, to—”

“Yes, I understand.”

The levers for the window cranks had been removed to keep things closed because of covid. She went to fetch one and came back.

“We’re not supposed to, but…”

“I know she’d like that. Thank you.”

How it was and how it is. How it’s meant to be. Forty-four years together, people. The thing that I was born for, plain as day. This time, this place, this woman. Simpler than I ever dreamed it was. If only I had known!

Dear Friends: A few links…

• I’ve written and posted an obituary here.

• For photos of the last eight years of our life in New Mexico (posted chronologically, newest at the top), see my SmugMug gallery.

• You’ll find hundreds of posts about us at this website by using any search field (“Kathy,” “wife”, etc.) or choosing a Category or Tags to search. Use your imagination. Some of them are in the Top Posts category linked in the menu bar.

• Most recent articles from JHFARR.COM are cross-posted at my Substack newsletter, which you can subscribe to for free.

• Washington College President Powell’s letter to WC alumni is available here. I urge everyone to read it to learn the full breadth and depth of Kathy’s academic career.

• There’s an email link for me on the “About” page.

Thanks for your comments. I know she’s read them all. – JHF

.png)