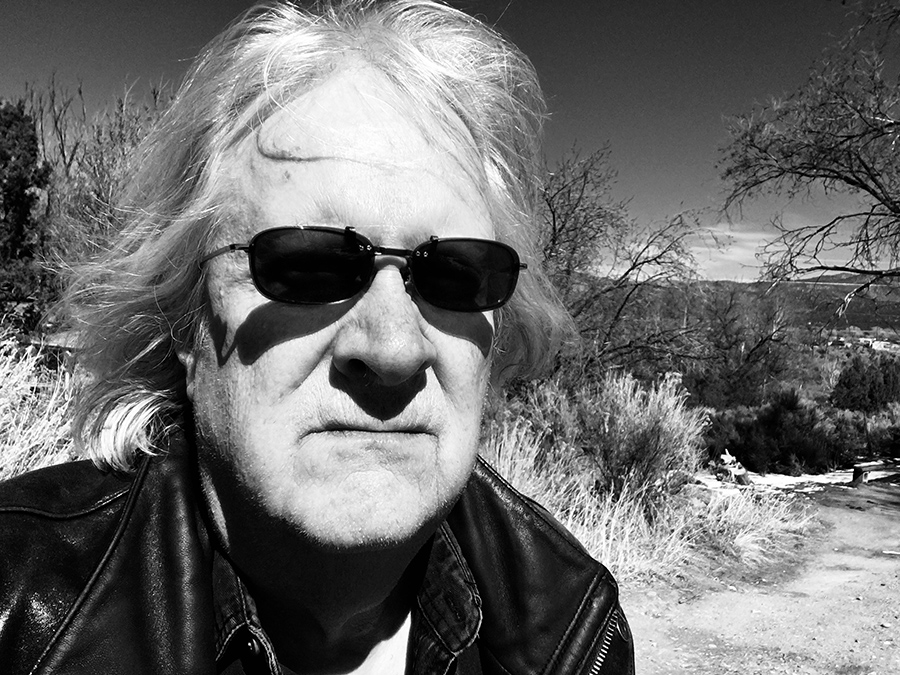

One of the greats. Warren Zevon in top form. The lyrics are oddly…pertinent, as well. More on Zevon here. He died of lung cancer in 2003 at age 56. Gray-haired me looks at this and thinks, I want my muscles back. Oh the young men. The young, young men.

Hiking out here is like having a couple hours off-duty from your flying saucer on another planet. So beautiful and dangerous. It’s over six hundred feet down from this location on the Rio Pueblo, at least eight hundred on the Rio Grande. The trail to get to this spot runs along the edge of the cliff for hundreds of yards at a time, no place for big stupid dogs or wild children. It’s a double-track trail, what I’d call an old jeep road, and I usually hug the inside path. Even with the distance above the river, you can hear the roar of water crashing over rocks like high desert surf. That’s Pueblo land over there, that looming mass to the west (right). The exposed Precambrian rock is over a billion years old.

We watched a small herd of bighorn sheep on the other side of the chasm, grazing on a grassy slope at the very edge of oh-my-god. You can spot them by their big white butts that shine in the sun. I was concerned that I might spook them, even at that distance, and that one of them might fall. Projection, no doubt. But they could surely hear us in the still, dry air and eventually shifted just enough to put some trees between us.

It hit me after midnight as I lay in bed, wondering about the magic beans I’d lost and where to get some more. All my life looking for a strategy, the key, a miracle to ease the pain and keep me warm.

During my senior year of high school in New York, everyone was choosing universities and plotting out their lives. I ended up choosing one, too, from a pile of catalogs in the guidance counselor’s office. All this undertaken entirely on my own, of course. My parents never offered one word of advice or even mentioned college. Raised me like a plant, they did, and sometimes I got water. But after years of nothing but straight A’s, righteous accomplishments in science, history, English, and sometimes art, blow-out SAT scores, all of this in two countries, five states, and moving over forty times so help me God, there was nothing I wanted to be… (Once upon a time I would’ve flown B-58s, but not with glasses.) Every “occupation” looked restrictive, anyway. I had everything I needed, so it seemed, right there in my head.

You may well imagine how things rolled on from there. One surrendered and adapted, one rebelled. Things were done and said, astonishing scenes were witnessed. Always intuitive, driven by passion, carried along with the tide. No one will ever figure all this out or care, so if I want to see it for myself, I’ll have to write my autobiography. (Or not!) That’s common writing craft advice. Writers, if I am one, are supposed to do a lot of things. I follow a Twitter account that tweets pithy observations and advice from famous authors’ interviews. Some of them are relevant. Some are brilliant. Some are just plain wrong.

One of the best writers I’ve ever listened to in person is Rudolfo Anaya. I was curating a writer’s series for the “Society of the Muse of the Southwest” here in Taos. Anaya was the guest of honor and gave a talk that killed me dead and brought me back to life again. It was all about his struggle to be “normal” and how miserably he’d failed—how he yearned to be an old man in a bass boat with a gimme cap and beer but knew he’d never make it. In the end, he realized he was actually this important thing, an accidental-dedicated-weirdo-medicine man (my words), or as he put it, at his best, a shaman of words… At the time, Anaya was about the same age I am now.

In my own quest to be somewhat normal and survive, I’ve been a college instructor, woods hippie, construction worker, musician, songwriter, office manager, sculptor, painter, bronze caster, cartoonist, and professional loner who sailed the tidal rivers of the Eastern Shore of Maryland. After marrying my college professor wife, I had a high old time doing most of those things all over again, only with less worry and better food. Moving to New Mexico meant it was my turn and I gave it a helluva go, riding the digital content creation wave as a pioneering columnist, news writer, and editor, until that scene blew up with the infamous “dot.com” collapse. Web designing came and went. I wrote some books. Since then it’s been a wild-ass tumble through the years. People died, the world went mad, and sometimes life was fabulous. I mostly twisted and burned, in the process blaming everyone from my parents to my analyst to the dark underbelly of this place and everyone who had it easier than I did.

The former college professor is still my darling wife. (My private room in hell has not appeared.) I love her like a monster and promised us a home. Everything I need is still inside just like it was a million years ago in high school, but there I was in bed with the old familiar terror seeping in and nothing, no one, to depend on. Suddenly there was a shift. I felt a click. The words came into focus: “I am my own guru.” Damn. That’s it, that’s all. That’s how I heard it. Just me standing here, holding the flag. The bag. Whatever. Now I know why I’m supposed to kill the Buddha if I meet him. It’s not out there, it’s in here.

“Do you really want to leave this place?” the visitor demanded. The question was surprising but perhaps a probe. Both of them, however, spoke of ancient energy that wouldn’t let him go. “I can feel it,” said the visitor again.

Not fifty yards away was an entrance to a kiva that some poor fool had long ago converted to a dwelling with a skylight and a stove. Who could live like that, though, underground, and why? Were there more chambers or a passageway? The surrounding landscape was so full of pot shards, he’d long stopped collecting them. Some weeks before, a work crew excavating for a water line uncovered thousand-year-old human bones. Houses on the road askew on shamans’ graves… What part of him accepted perfect punishment? He’d felt a similar great hurt beside the road in Massachusetts once and entering Ohio underneath a big full moon, but those were in a car and passing through. Living over blood is different. Something seeps into the half-awake, wears old clothes until they fall apart, and no one knows your name.

“Yes,” he said, “of course! But not from this place into nothing…”

“Of course,” the visitor replied.

[To be continued, possibly]

It’s like dropping out of hyperspace onto an unknown planet. This spot is six miles and a thirty minute hike from where we live. The image above, a familiar view but never from this spot before, is actually a video still, which explains the aspect ratio (16:9). I call it “Flight Deck” because not only could you land here, but if you were in this space, if you occupied it with your soul so that right here was your cockpit, you could fly to almost anywhere.

.png)