For the last two decades of her life, every time I visited my mother, she’d shove a book at me called “How We Die.” Helen loved discussing her demise. I never could figure out why, except as a way of making me feel sorry for her. That wasn’t it, though. She was really trying to kill me. Quite unconsciously, of course, but it was cold and terrifying every time. She wanted me to read the signs of physical decay inside myself. Can you imagine?

I had a wondrous dream the other night in blazing technicolor, sharp as any movie. I was at our old home in the country back in Maryland, the one my wife and I bought back in ’89, but it was different: much larger, tall, and beautiful, more formal, “higher rent.” The floors were covered with dark red tiles, almost maroon, thick glazed ceramic tiles four inches on a side, with deep-cut beveled edges. (Rolling a vacuum over them would have been quite noisy.) The color of congealed blood, it occurs to me. There were two female (anima) figures inside the house, women who were old friends from the area. One I witnessed puttering happily through a window and I think we waved, the other I hugged tearfully on the back steps, saying, “So much water under the bridge…” Her dress matched the color of the tiles. She hugged me back but cooly, looking off into the distance.

The yard outside was striking. Beautiful green grass that stretched forever like a park, with immense, impossibly tall deciduous trees. They all had straight, clean trunks (no branches) that reached up to crowns of bright green leaves against a clear blue sky. The trees were absolutely stunning.

As I walked around the house, it changed—white siding with no windows—and I came across two very different trees. Both of them were low and old and heavy, leaning partly over the lower portion of the house, with gnarly twisted trunks and hardly any leaves. The bark was peeling like a sycamore. The first one was severely tilted but supported by a sturdy, hollow steel pole like a flagpole that tapered toward the top. The heavy bottom end was anchored in concrete in the grass, and the pole—more like a pipe, really, about 12 inches in diameter and painted silver—extended upward at a 45° angle to meet the trunk. An expensive, professional job, I thought. The undertaking of a government, perhaps.

The second tree was lower and more fragile. High up on this windowless side of the house, a heavy branch had almost punched a big hole in the siding from swinging in the wind. I could see the indentation, round and deep. That one needed cutting, I decided, or the next big storm would punch the hole completely through.

There’s a lot to unpack in this one, but it isn’t hard.

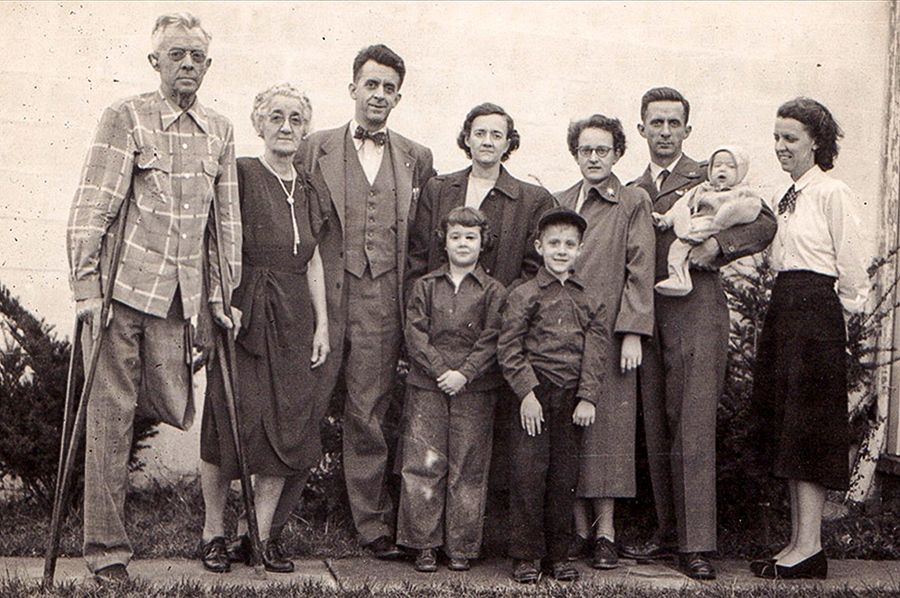

In grossly simple and symbolic terms, the house is me, my body. The anima figures are my creative side, my muses. (Having two of them is somewhat odd and needs reflection.) The otherworldly tall straight trees are my true self, and I’ve seen them before in dreams. The older, gnarly trees against the windowless (unconscious) siding are my parents. The tree supported by a silver pole would be my Air Force father, the one that’s almost knocked a hole into my head is Helen [koff], and now I know why I started this thing off with her!

.png)