The spiders were still hibernating. The cobwebs on the ceiling quivered in the drafts. Juan del Llano scrunched over far enough to squint at the clock: 7:57 glowed green through the dust. The old black Sony she gave him for Christmas 15 years ago. Did people really used to wake up to the radio? He tried it once or twice to get up early to drive to Albuquerque for a flight, before he had an iPhone, when she was far away in cold Dubuque. As he eased back now against her and felt the warmth, she gave a little moan of recognition and the morning edge. A song or poem he’d never heard before kept cycling through his brain:

Empty my head

empty my head

roll it all out

on the ground

empty my head

just like I’m dead

except I’m still

here all around

Yesterday at cocktail hour. Juan had coffee, not tequila, six days past a bad boy molar. He remembered how it cracked. She drank lemonade and stared down at the carpet.

“I’ve had it,” he said.

“Me, too.”

No need to dig deeper, just The Situation.

He knelt down to build a fire in the Ashley. Where would they be in the old adobe without that hippie mainstay? Back in the woods in Arkansas some 50 years ago, he’d read his battered Whole Earth Catalog and dreamed of one. (Back to the land we go, hi-ho.) Seven or eight lifetimes passed between. Sagittarius rising or growing up an Air Force brat? Burn, you stupid motherfucker. The local paper he’d crumpled up for starter fuel was oddly slick and nearly fireproof, but soon the piñon flared, the stovepipe signaled hey look out with a crick-crick-crick, he turned the draft clear down, and twilight in el Norte faded into night at three degrees.

Why was it every time he reached his limit, yeah-yeah, it was already winter? Abundance thundered in the void and all he needed was a rain dance. He bought a fancy German vacuum cleaner, red faux leather sneakers, and real leather ones in black. He was so tired of the deprivation. Voluntary, mostly. Tired of dust, dirt roads, the neighbor’s dogs, what passed for life in wartime Taos. All around was madness: lunatics and fascists, zombies of his past. The old man’s life advice had mostly been of things to be afraid of, stuff you couldn’t have. How to bait a fishhook, now that was helpful. Which way to turn a screw, how to drive a nail. Nothing’s ever black or white. No one goes to hell. Surely goodness and mercy would follow him all the days of his life, and he would dwell in the house of Juan forever.

The oral surgeon had just left. Juan felt no pain except the memory of the cold steel forceps in his mouth. “Do you want to keep your tooth?” the assistant asked. That would have been nice, he almost cracked, but she was much too kind and smart to torment. (Move through life and be a dolphin, never leave a wake.) Curious, he sat up, peering at the tray. Ah yes, the old gold crown, still attached to a jagged piece of tooth with a bright red line of blood along the edge. As if he’d had his ankle severed by a bullet and they offered him his shoe and foot, he thought.

“No, that’s all right.”

Five hundred eighteen dollars, paid by debit from the chair. Like being maimed inside a spaceship, so you wouldn’t even mind. He didn’t, actually. The tooth was gone, he’d paid with fairy dust. They had it down, all right.

Out the door, still biting on the gauze. He and his wife were in the truck this time, his ‘01 Dodge Dakota with the big V-8. When they’d left the house, the Vibe had started up all right but cranked too slowly. Sensing trouble, he’d switched seamlessly to the gassed-up 4WD and off they went. The next day it was snowing when he tried the Vibe again. Not even a solitary solenoid click. Aha. It took three days with breaks to pull the old battery, take it to O’Reilly’s, and install the new one. There was still some jiggering with the hold down J-bolt to be done, but Juan had found the answer on the internet. That night it snowed again—five inches—and he finished in the morning. Six days passed before the Miele arrived from Amazon. The Vibe was still snowed in.

People he saw online went out and did things, never mind the plague. But in the cold and wind he lost his nerve. If only he could keep his thoughts from killing him. Did he not have a golden flaming Jesus riding on a tiger in his heart? He vowed to take the fancy German vacuum to the cobwebs, suck the sleeping spiders from the cracks, and wear the bright red sneakers while he did. Empty his head, goddammit, motherfucking blank, and be here now. The Miele was so German. Everything was click and turn and pop right out or slide right in. The motor spooled up slowly like a Zeppelin coming over the hill but sucked with black hole fury until the bag half-filled and flashed a warning. The filtration was so efficient, the dirt so invisible and deep, it did so after only half a room. No wonder the house was “impossible to clean.” Their old vacuum moved dust like a leaf blower shifted leaves. Every step they’d ever taken on the threadbare carpet only raised it up into the air to fall again on top of everything and down into their lungs, food, hopes, and dreams. You want to be free, buy more bags. Even half-filled, clogged, and signaling nicht gut, it yanked yards of greasy bullshit off the wall and antique shotguns in the corner. He moved one aside. The biggest cobweb spider he’d ever seen sat snarling in a clump of tiny victim husks, but not for long.

Magnificent and mundane all at once. The vacuum was a sign.

A few days later Juan del Llano was on a tear deleting photos. In the old days he’d have filled another shoebox and stashed it in the closet but there was neither that nor shoebox to his name. Old adobes didn’t come with closets, just two pegs behind the bedroom door—one for a Sunday outfit, the other for the work clothes—that’s why someone invented the trastero. (They had a pipe suspended from the vigas in the bathroom.) But the 21st century came in via coaxial cable from the wireless internet receiver on the roof. He laughed recalling his surprise the day the ISP techs pulled out a portable drill and punched a hole through 18 inches of old mud bricks and never asked. Not that he cared, but damn the thing was easy. So that was how he started burning old tired pictures off the SSD… There were so many of the same things: canyons, mountains, snow, his silly face, the old dead cat, the tires on his neighbor’s roof. Delete, delete, delete. Another gigabyte, hooray.

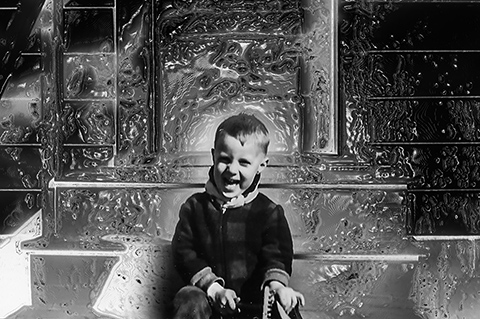

He lingered over one shot, though. A scanned image of his five-year-old self sitting on the back steps of his mother’s sister’s house in Maryland. The one he spent the night in once with all his cousins sleeping in the attic, the old wooden building he’d have called a farmhouse now but this was on a quiet street beside the railroad tracks where bad boys and girls put pennies on the tracks to get them squashed. He’d done it once but gotten scared—what if it made the engine jump the tracks? There was a willow tree in the front yard. His Uncle Buddy cut a stick and made a whistle for him once the way you could because the bark slid nicely off the bright green wood. One time everyone was eating bologna sandwiches on white bread at the kitchen table, baking in the humid June, when the iceman (think of that) came up those same back steps, pulled an ice pick from his overalls, and chopped off corners of the block for them to suck on.

He stared hard at the photo. Something snapped and he felt clear and strong and knew that he could manage.

Hi, Juanito.

(Hello, Juan.)

Magic at his fingertips, mercy in his heart.

.png)

That picture of 5 year-old you is adorable! Don’t ever delete it.

Wouldn’t dream of it.

You must log in to post a comment. Log in now.