Sometimes a cow is just a cow, unless it’s a heifer or a freemartin or a cattlebeast. For that matter, these might be steers. (Those are all legitimate terms, by the way.) I usually don’t pay that much attention unless we’re talking about bulls or have to steal some milk. In that case, you’d better get it straight. The only certain thing is that most of these will end up on a bun, which makes me sad and hungry.

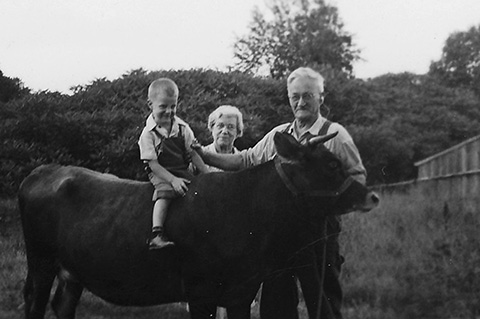

For someone who doesn’t know much about them, I have a special relationship with cows. Er, cattle. Everywhere I’ve ever lived, if there are bovines on the other side of a fence, I’ll go up to them and try to communicate in cow-speak! (The beasts above were very paranoid, however.) Once when I was just a lad, my great-uncle Herbert in New Hampshire showed me how to milk one. I’ll never forget the sound of the stream of milk hitting the bottom of the metal bucket or how it steamed in the cold air in the barn. Later he sat me up on top of one (below). That’s him with Mrs. Ellsworth, his “housekeeper.” They were something of a scandal, but that’s the way it was with him. Quite the man, my granny’s older brother.

I was surprised how warm the cow’s back was

When we first moved to New Mexico, we lived in the tiny mountain village of San Cristobal. (The rest of America has absolutely no idea what that’s like, but check out Buffalo Lights for enlightenment.) Everything is different here, even the ungulates. I’d always see these awful-looking cattle in a wretched field and finally asked our landlady about them. Here’s a third-person narrative I wrote at the time:

“Those are THE cows,” his landlady explained.

He’d wondered about them, the small herd of a dozen or so rough-edged beasts he saw nearly every day. They were not quite like any others he’d ever seen, with their thick, curly, dust-colored hair, “nappy” as she described them, and their nasty-looking horns. They usually hung out just behind the rusty wire fence on the south side of the dirt road leading up the valley. Every evening a woman came down the hill with a bale of hay in a wheelbarrow and heaved their dinner into the near end of the narrow little pasture. The ground here was bare except for cowflops and a few rusty pieces of machinery—an old truck axle, a wheel or two, and three-fourths of a dead tractor. But the cows didn’t seem to mind.

“They’re descendents of the original herd brought over by the first Spanish settlers,” she continued. “An old breed they’ve kept going all this time.” Well, no wonder! That accounted for the scruffy, wild, yet tired look these bovines had. THE cows, indeed.

.png)

When I first began to read this post, Buffalo Lights came to mind. That and Taos Soul have permanent places on my bookshelves. Not in the sense that I never take them down permanent, mind you, but more like permanent as opposed to Fifty Ways To Light A Fire permanent…just in case it matters.

Like you, cattle have always been a part of me in some way or another. I don’t know if it truly began with those long walks with my mother through the tall rye grass and white-faced Herefords, or if it was when my dive through the rails of a pipe fence came just a second before that Brahma bull tossed me over the top. Like Donny Gay used to say, “Only he and the woman who does his laundry knows how close that bull came.”

These days I just know those critters are near by every time the wind blows down the South Platte River valley. I can only eat steak when the wind blows north.

Feedlots, yow!

Love the Donny Gay quotation.

At some point I’ll put out a print version of Taos Soul. Right now I’m trying to get some other things off the ground.

“The only certain thing is that most of these will end up on a bun, which makes me sad and hungry.”

You sum up the contradictory duality of existence eloquently!

“Awwww…”, but simultaneously “Mmmmm…”

History on the Hoof, just walking about there.

Years ago I visited the Lama Foundation in San Cristobal. Beautiful place.

You must log in to post a comment. Log in now.