There’s no way I can tell you when I came into possession of this thing, but perhaps my wife remembers.

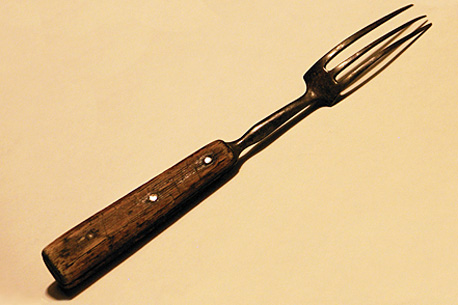

It may have been in a box of family relics Granny gave me, who knows? But it’s a typical Farr family artifact, because it’s totally plebian: a kitchen fork… I know it belonged to her mother, and I think it belonged to hers, which dates it to the early 19th century, say 1810-1820. The amazing thing is, we use it all the time! We throw it in the sink to wash. It’s my favorite kitchen tool, and I hunt for it in the drawer whenever I need a “stabber.” I don’t know when we absorbed it into our regular utensils, but we did and never looked back. Well, until now. Just look at this:

My grandmother’s family is from West Virginia. Her father was a circuit rider, a preacher who rode his mule to a different Methodist service every Sunday. I used to have his saddle bags (long story). While I’m proud of that tradition, my mostly intuitive sense of him from the little I was told is that he was pretty much a joyless, tyrannical cheapskate, but then that went with his brand of religion: “shoutin’ Methodists,” they called them. None of these people ever had anything fancy or luxurious, and if they had, they’d have felt guilty! I conclude that this must be an ordinary object for the time, and if they passed it down from daughter to daughter, it was because they didn’t want to have to buy another. Nothing special then, or is it?

Look at the graceful design: the way the fork itself is fashioned, the riveted wooden handle that feels so good. It’s a pleasure to hold and contemplate. Practical, yet resonates on many levels. This is truly a very fine fork, and someone made it. See the image above? The thin shank between the two halves of the handle is actually tapered, which tells me someone pounded it flat on an anvil. Though a one-of-a-kind, it’s still utilitarian and couldn’t be anything more, coming from my family. Put all of this together, and there’s a stunning message…

“MY GOD, WE’RE USING A 200-YEAR-OLD FORK!” was the first thing that came to mind. The second was that no one I know can do this anymore. Make a fork, that is. (Could you?) The third was that we’re so advanced and all, but nothing ordinary folks could buy today would ever be this good or last this long.

Considered in the context of what a throw-away society has meant for social justice and the Earth, this isn’t just a fork, it’s an indictment.

.png)

What’s really good about that fork is that you’re still putting it in your mouth in the same way and for the same purpose as did ancestors of yours 200 years ago, thereby linking you to all the lost times and places which led to you. My wife has a small wooden chest made by her own great-great grandfather, which we use as the repository of some of our own most important papers, as no doubt this bewhiskered and suspendered old gentelman did and as did someone in each generation of his numerous children and grandchildren. Every time I open one of the little drawers to put in a piece of paper with the year 2010 printed on it I think of that lost world – no running water, no electrification, no internal combustion engines, no books except the Bible, no teeth in the heads of folks above the age of 30 and many deaths prior to that age. I think of the sternness and resolve on their faces on a few old photographs. These people lived without much ease, and they thought life would never change (notwithstanding such newfangled inventions as photography), as indeed it hadn’t changed for centuries in its essentials for their kind or those who came before. It didn’t change much for several generations after them. That was pretty well the world my father grew up in in rural Missouri.

Despite our post-modern angst, our world may not be so different in the essentials even as we toddle toward our graves in the present century. Nor will it change much in those same essentials for our children and grandchildren. The dentistry will be better, I reckon.

Our great-greats had angsts of their own, and perhaps for more reason than we. That little fork, that little chest, remind us of them and are somehow a comfort – to you in your way and to me in mine.

Thanks for this, Ken. I do appreciate it. However, you may be wrong about no teeth after age 30. These people weren’t eating a lot of sugar! And a lot of them lived a good long time. In my own family records, there are plenty of that generation living longer than most people do today, although there are also whole crops of children wiped out en masse by diptheria, flu, etc.

But they could have forks that lasted long enough to pass down to their kids… Try that today with Chinese junk! And that wooden box of yours was probably made from old, fine-grained virgin timber, the kind of wood one just can’t find today, because we cut down all the big trees. Same thing for the handle on my fork, which has survived dishwashers and unending abuse for years.

Given my family, my attachment to the fork isn’t really sentimental, though. Iconic, perhaps. 🙂

I don’t reject “sentimental” as a description but I prefer to think of my attitude towards the artifacts and people of the past as simply “historical”. The handcrafting of beautiful utilitarian objects was characteristic of a certain era. That era has largely passed. We moderns tend to want to cherry-pick the past for the things we like in it (crafts and simple living), as if those things could be detached from the things that surely accompanied them – narrowness, limitations, stultification, deprivation. We think we can make up a future of all the best elements of the past. We make a stick with which to beat the poor inadequate present. I guess it’s the old Marxist in me, but I always am prone to see the delusions of utopianism in a-historical thinking. The present may not be such a great place, and God knows what the future will be. None of this troubles me very much. What I mainly see is the continuity of the human predicament, worked out over and over again in all ages, with all manner of utensils, furniture and paraphernalia. This to me is moving. That little fork is the bearer of much human history. If it could speak, what tales it would tell. –You are indeed an effing genius, my friend, for having extracted such poetry from such a humble object.

Yes, it IS effing brilliant. Thanks.

You’re welcome. It’s good to judge one’s own work first, too, isn’t it? 🙂 Of course, the FORK is the star.

And you know, it just blows my mind that we have lost the ability to take care of our basic human needs. Who the hell can make a fork? We’ll all be eating with our fingers in a goddamn cave someday. Sad business, really.

This is great. My wife has a knife that was her grandmother’s that she brought from Venezuela. It has a bone handle, and is very simple — but works. I love stuff like this that meets the precise same purpose as it did 200 years ago with no real reason to replace. Old technology rules.

I’m working out of metal shop making tools and prototyping a bike generator. I think my next project is going to be a fork. This one is cool.

Hi Tommy, glad to see you! (For everyone else, check out this man’s website—you’ll be glad you did.)

I wish I knew more about the fork. The more I think about this, the more deeply I’m affected. We need to be able to do things like this. Most of us are so damned vulnerable and at the mercy of the system. Kudos to you and what you’re doing at your Freedom Guerilla site.

Onward!

UPDATE: And as long as there’s no one else in line yet, I have to report that I’ve taken the 200-year-old fork out of daily use, at least for a while. Out of respect, let’s say, and while I digest all this. My wife replaced it with a late 20th century Japanese version that looks durable enough, but isn’t nearly as beautiful to look at or comfortable to hold. Might last a couple of centuries, but it looks too expensive for the likes of Reverend Hamilton Young from Parsons, WV!

Johnny, I find this fasinating that you have a fork that is that old. It just shows you how short our lives are on this earth. I am assuming that this is a Farr heirloom, not a Masson. Also to have such a godly inheritence from your Great Grandfather is worth much more. I also come from the shouting Methodists. I have many stories from my mom, your Aunt Aolia telling us about the horse and buggy rides to Orems Methodist Church and the barn that they tied them in during the service. The really old church had men enter from one side and women from the other. They also had a row for the shouting people. They called it the Amen corner. Also the circuit preacher that came once a month. Do you know any history on the Masson side beyond Grandmom Masson. I know she was a Voltz and I believe she met our Great Grandfather on the boat coming from France.

I have two forks like yours and would like to get rid of them as my kids will throw them away some day. Do you want them??

But they may be valuable if they’re as old as mine! You might want to check… If you’d like to give them away, though, sure. Just email me and I’ll send you the address. 🙂